We're building a tunnel for tens of millions of gallons of sewage. Here's what it looks like.

You can't tour a sewer tunnel construction site 120 feet under Cleveland. So we did.

One hundred and twenty feet underground. Tunnels large enough for dump trucks with room to spare. Towering contraptions and train-length machines moving thousands of tons of earth to protect Lake Erie.

The depths of the Shoreline Storage Tunnel construction in progress is worth a closer look. But to understand the true scope and scale of this project, let’s look back before we look below.

Cleveland has long had a combined sewer overflow problem. Sewers designed in the 1800s did a great job collecting and moving stormwater and sewage in the same pipe. But as development advanced and population grew across the region, even well-maintained infrastructure couldn’t keep pace with urban stormwater runoff, which meant more and more combined sewers were reaching capacity during storms and discharging waste to the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie.

In 1972, combined sewers were releasing nine billion gallons of combined sewer overflow to the environment every year. Through significant investment and improvement, we cut that volume by more than half over the next 40 years. But there was still more work to do.

That’s when Project Clean Lake came to life. Our 25-year construction program began in 2011 as we committed to another 4 billion gallons of CSO reduction by delivering treatment plant expansion, green infrastructure installations, and a series of seven huge storage tunnels. The Shoreline Storage Tunnel is one of them, number five of seven.

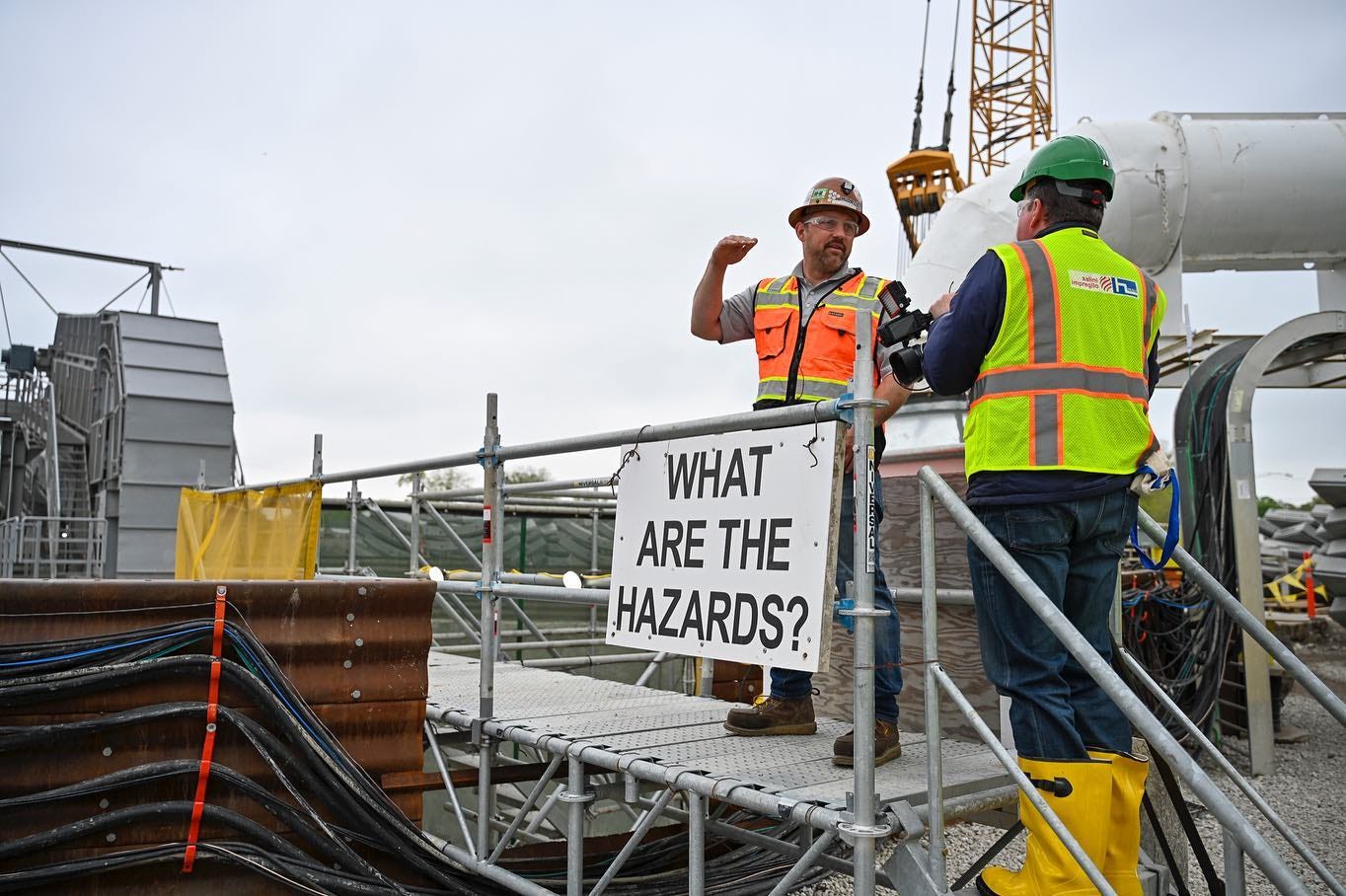

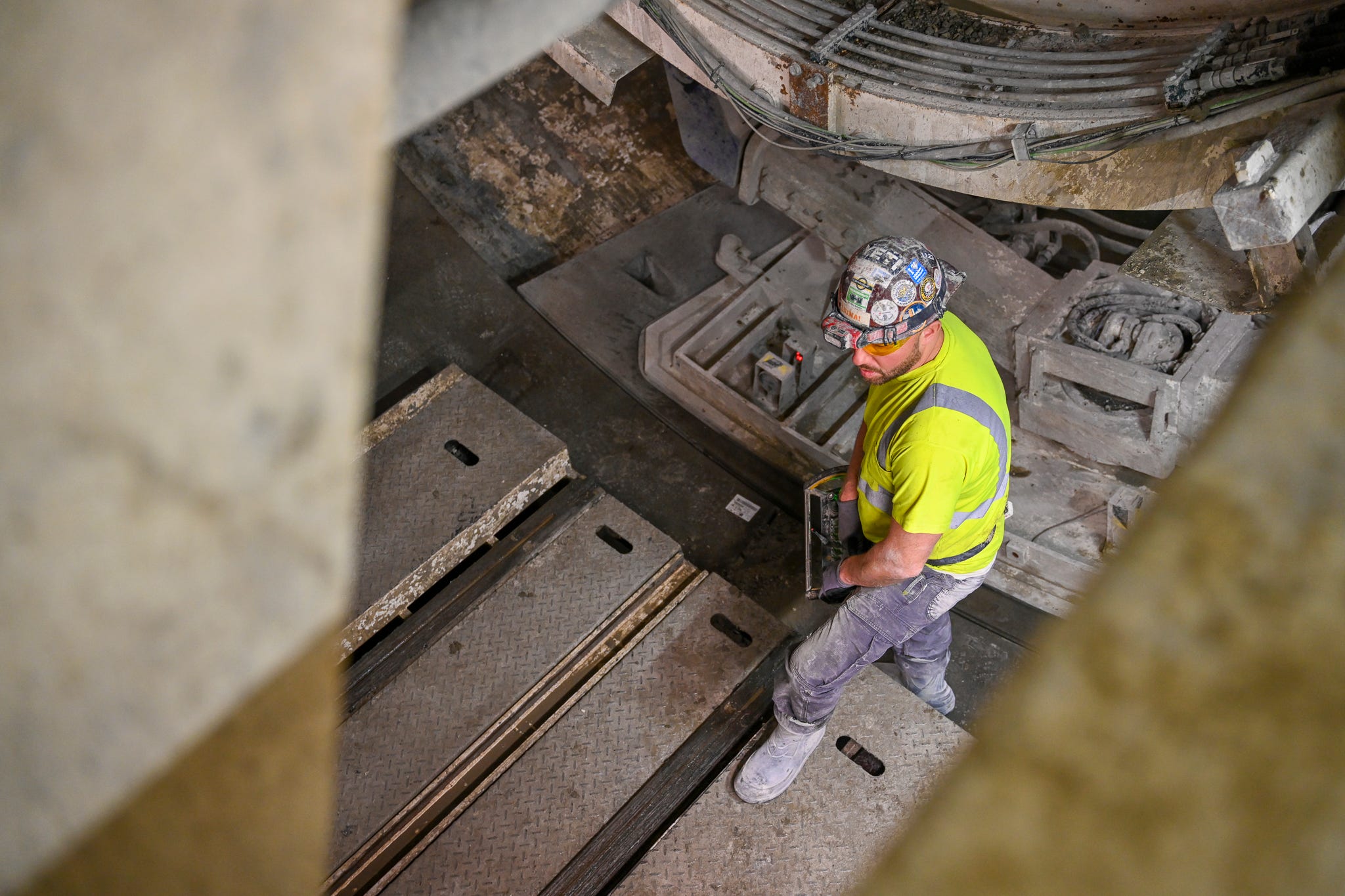

Our Communications Specialist Nicole Harvel recently took a long walk down to the bottom of the construction shaft, camera in hand.

As of May 8, just over 1,000 feet of the nearly three mile tunnel has been mined. This soft-ground tunnel (the other four Project Clean Lake tunnels so far have been bored through Chagrin shale) is being dug and constructed in six-foot increments along Forest Hills Park at E. 110th to E. 55th Street.

The single-pass approach is a marvel in and of itself. The tunnel boring machine, a labyrinth of hydraulics and catwalks and pipes and power, creeps laboriously along, carving out the tunnel alignment before it.

In its wake, robotic arms and human hands work together to piece the tunnel lining together one huge concrete segment at a time.

Six segments connect at their ends to form one ring, six feet wide and more than one foot thick. The entire tunnel will consist of more than 2,300 rings and 14,000 individual concrete slabs when the tunnel is complete in 2026.

What about the mined material? When boring in rock, the shale is carried via conveyor belt up and out of the shaft to towering mountains of spoils at the surface. But instead of piling rock, imagine trying to build a mountain of toothpaste. That’s what Shoreline’s tunnel boring machine is conveying out behind it.

The solution at the surface had to be different. For this tunnel, a brick-lined pit is filling with a pasty rock slurry around the clock so trucks can fill and refill more efficiently within a much smaller project footprint.

Project Clean Lake is the largest infrastructure project most northeast Ohioans will never see first hand. Ultimately the Shoreline tunnel will have a capacity of more than 40 million gallons and mitigate 350 million gallons of combined sewer overflow from reaching Lake Erie in a typical year.

Photos and videos by Nicole Harvel.

I wish the film clips worked.